The Scottish National Gallery in

Edinburgh is composed largely Old Masters—huge canvases by Velázquez, Titian,

Raphael, and Rembrandt leanings down on the viewer off scarlet walls. The rooms

are big and the ceilings are high; it’s an imposing gallery. But, at the far

end of the gallery, a staircase leads up to a much smaller, less showy series

of rooms that host the gallery’s small permanent collection of 19th-

and 20th-century artwork. Among the painters gracing the walls there

are Monet, Cézanne, and the American painter John Singer Sargent. There’s only

one Sargent painting in the national gallery’s collection and it is on

permanent display: “Lady Agnew of Lochlaw.” I visited the painting three times

while in Edinburgh: the first time, I hardly noticed it; the second time, I sat

in front of it for twenty minutes, scribbling thoughts in my notebook; the

third time, I went to the gallery to see only

it, nothing else.

|

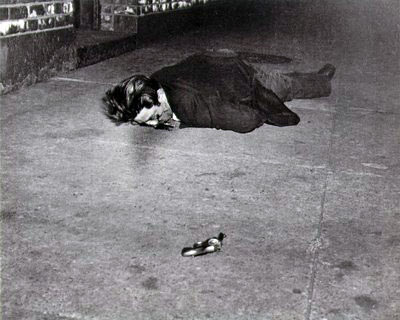

| "Lady Agnew of Lochlaw"; John Singer Sargent; 1893; National Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland |

I’ve provided you with a photo of

the painting above, but, as is always the case with pixels versus paint, the

piece comes out the digital end of things a little worse for wear. That’s

partly an excuse—if it doesn’t have the same magnetic pull on you that it did

on me, then I’m willing to blame the technology. It’s also another kind of

excurse—a kind of embarrassment: you see, I don’t know that you’ll feel quite

the same way about “Lady Agnew” as I do even if you did see it in person, not one a computer screen.

In thinking about my reaction to

this painting, it struck me how alone an experience with a painting is. You

can’t share your look with anyone;

it’s a moment just between you and the painting and it’s impossible to put into

words. The second time I saw the painting, it was the same draining of emotion

that I’ve felt at the end of great novels—a kind of emptying—as if the read

world surrounding the novel had been drained of color. Everything else seemed

to lack.

Someone—in this case, John Singer

Sargent—figured how to capture that dizzying feeling of great fiction, the elation

at the end of the story, and distill it into a frame, catching it there like an

insect in amber. That sounds hyperbolic and silly, but there’s no easy way to

explain it. Everything else looked uninteresting

once I had really seen “Lady Agnew.” That might trouble some people, given that

Monet and Cézanne graced the walls of the same room, but when I looked over at

these paintings, I felt only appreciation,

none of the same sense of experience

that I felt with Sargent’s painting. I had lived, however briefly, within that

painting. It changed me—and the way I think about art.

~

This past week has seen me (much

as you could have predicted) in a major John Singer Sargent phase. I thought,

somehow, that knowing more about Sargent would bring me closer to understanding

this painting and my reaction to it. I read about Sargent’s early life with his

family in Europe and his interest in art as a child. I read about Sargent’s

training in Paris and his work under mentor Carolus-Duran, who introduced

Sargent to techniques drawn out of extensive study of Velázquez’s works. I read

about his later successes and his even later disdain for that same

portrait-based success. I read about how art critics have long been at odds

over how Sargent should be classified: as a member of the avant-garde

Impressionists who retained ties to the academic school or was he more of a

black sheep figure of the academic school, who took on Impressionistic

techniques without ever fully entering their world? I delved deep into the

minutia of these arguments, hoping for a clue.

In her concise, insightful book Interpreting Sargent, Elizabeth

Prettejohn argues that the dependence of critical discussion on these

categories—academic vs. avant-garde—has actually restricted our understanding

of Sargent’s work. Prettejohn offers instead that the tonal system Sargent

learned from Carolus-Duran via Velázquez was a third way; it was neither

the academic painting of the Paris Salons nor

was it the avant-garde of Monet. Sargent’s tonal method included neither the extensive

preliminary studies and diligent finishing of the academic tradition nor the

patches of color method of painting that was de rigueur among the Impressionists at that period. Prettejohn sets

up Sargent not as a middle-of-the-road man, but as someone who forged a

different road altogether.

~

But that didn’t get me anywhere.

None of it did. I can confidently say that I love Sargent more fully now that I

know more about his life and the context of his work, but I am no closer to

‘understanding.’ I thought—wrongly—that knowing the details would be the way

into the painting. (God is in the details, is he not?) I don’t need to tell you

that it didn’t help. To learn about how Sargent chose to arrange the posture of

his subjects—often painting them leaning and at ease instead of properly erect

as the art establishment would have dictated—was to understand the genesis of Lady

Agnew’s curious pose, but not to understand me looking at the painting. And

even if someone (Prettejohn! Please!) could have explained to me her

inscrutable expression—that direct, confident gaze leveled at the view, coupled

with her lips that verge on either a smile or a frown—it still would not have

led me to understanding my own reaction. What is she thinking? What’s going on

behind those eyes? Are those even fair questions to ask of the painting?

~

In her book, Prettejohn addresses

just that—the crucial problem of psychology. Many art critics were dismissive

of Sargent in the latter part of his career and after his death in 1925; they

shrugged off his work as lacking in ‘psychological depth.’ In the wake of Freud

and the boom in psychoanalysis, painters and visual artists—especially

portraitists—were expected to imbue their subjects with a psychological

profile. It would be anachronistic, Prettejohn points out, to apply

psychological criticism to a painting like “Lady Agnew.” Freud—and the artistic

fashions that followed—were simply after Sargent’s time.

However, there is still a case

for finding loosely psychological perceptions in Sargent’s portrait work. As

Prettejohn notes, the entire practice of portrait painting had already undergone

a revolution thanks to the rise of photography. By Sargent’s heyday, portrait

photography was already in full swing. If someone simply wanted a likeness of

himself, he would go to a photographer; he wouldn’t bother with a painter. So

when people paid Sargent for a portrait, they weren’t paying for just a

likeness; they were paying for something more

than that.

Drawing off the work of American

philosopher and psychologist William James (with whose ideas Sargent would have

been familiar as an acquaintance of William’s brother, the novelist Henry

James), Prettejohn argues that the ‘more’ is the subject’s ‘social self.’ In

his 1890 psychology milestone, The

Principles Of Psychology, William James, introduces the ‘social self’ as

“the recognition which [a man] gets from his mates.” James later continues, “a

man has as many social selves as there are individuals who recognize him and

carry an image of him in their mind.” Prettejohn suggests that Sargent’s

mission as portraitist of high society was to approach the portraits of his

subjects as more like portraits of their social selves. In most cases, this

perspective on Sargent’s work is especially fruitful.

~

Not only was Sargent’s era

interesting for the riotous change happening in the art world, it was also

notable for the sweeping social changes in Europe, especially in England.

Social boundaries that were once seen as stable and impermeable were suddenly being

fractured. Society was being turned upside down by a class of newly wealthy,

whose appearance threatened the inherited positions of the landed aristocracy. American

women who married into established European families, like Madame Gautreau (of

Sargent’s infamous “Madame X”), scandalized the social words of European

cities, reporters referring to them as ‘professional beauties,’ essentially a 19th-century

synonym for ‘gold-diggers.’ Social classes were subject to constant

redefinition and reevaluation.

|

| "Madame X"; John Singer Sargent; 1883-4; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, USA |

As such, Sargent’s task was to

document a world in flux. His portraits reveal not confident stasis—as

portraits of royalty by the Old Masters might have—but an encroaching insecurity

and anxiety. Critics have noted the strange, ‘posed’ forms of some of his

subjects; notice, for instance, the ‘pose’ of Madame Gautreau, the strain in

her neck and the awkward positioning of her right arm. These signs, Prettejohn

argues, are signs of the emerging ‘social self’ of Madame Gautreau. An American

woman who is not European aristocracy, part of her ‘social self’ is contortionist,

trying to play the part and make herself fit in. Several of his famous

portraits bear out this thesis, including “Lady with the Rose” and “Mr. and

Mrs. I.N. Phelps Stokes” (both of which I will hopefully soon see in the Met);

there is a deep insecurity lingering in the subjects of both of those

paintings.

But what about “Lady Agnew”? As

everyone else in Sargent’s greatest hits looks at least a little discomforted,

she exists in a state of odd ease. Why?

~

To tell the truth, I probably

haven’t dug deep enough. I shouldn’t come to hasty conclusions. Neither of the

two books I read on Sargent (the other, for those interested, was Sargent by Carter Ratcliff) addressed

her in any depth. There might be some detail about her ‘social self’ that I

could still dig up and explain it all away. But as of yet, I have found no key that

might help me unravel the curiosity of this painting.

The more important discovery is

the suspicion that nothing out there will fully explain my fascination—it will

remain like that moment at the end of a novel, except without any words to

latch onto…just a slouching figure and a suspect expression. And, as I knew all

along, words might not be able to do it justice, but, goddamnit, I’ll keep on

trying.