The dark stain of blood on the

sidewalk. The lurid glow of water hitting a fiery building. The observers of tragedies: faces twisted in pain, flushed

with fascination. The perfectly observed object: a gun, a hat, a shoe, a DOA

tag, a lamppost. Weegee—the photographic pseudonym of Arthur Fellig—was the

first master of news photography. Looking at his work today, with its

heightened, grainy contrast from the flash that he used, it reads as the

natural precursor to Hollywood’s film noir binge of the 1940s and 1950s.

|

| A still from John Huston's The Maltese Falcon, starring Humphrey Bogart (center); via britannica.com |

The worrisome part of Weegee’s

legacy for art historians and critics is, surprisingly, not the merit of his

photography or his gifted eye, but rather how his work sits on the walls of an

art gallery alongside Steichen, Steiglitz, Cartier-Bresson and other

recognized ‘art’ photographers. In hanging his photos on a wall, it almost feels as if we'd like to displace Weegee’s work from its original context. After all, he took photos not as a hobby or for the 'sake of itself,' but for money, for the newspapers. First and foremost, he was a journalist.

~

The impressive part of the

International Center of Photography Museum’s current exhibition on Weegee—Weegee: Murder Is My Business—is that

the exhibition’s curators never undersell that aspect of Weegee’s work.

Reminders are everywhere; supporting texts are careful to link his work back to

his life—that of the photographer on the beat, combing through the lowlife of

lower Manhattan, working out of the back of his car. Several of his photographs

are paired with the work not only of contemporary newspaper photographers, but

also the crime scene photography of police officers, pulled from New York City

archives, establishing not only a critical relativity for evaluating his work, but also creating a larger context for his work.

I've found that thinking about his work as occupying the space between the newspaper and gallery wall is immensely rewarding. Photography, perhaps more than any

other artistic discipline, suffers an extraordinarily large ‘gray’ area. What

photographs are art? Some of the most

famous photographs of all time are journalistic work, not really 'art' proper at all: Joe Rosenthal’s

photograph “Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima” and Steve McCurry’s “Afghan Girl,” to

name two examples. If “realism” is the argument here—that we appreciate the

wartime spirit and the social concern captured, respectively, by these

photos—I don’t buy it.

There is something that moves us

in these two photographs that is more than a simple curiosity being sated. It's not the mere transmission of knowledge. When

I see “Afghan Girl,” I do not think: "So that’s

what an Afghan refugee looks like." The viewing experience is nothing like that. I suspect that

no one—save those who know her personally—can look at that photograph and shrug

it off as mere 'information.' There is identification happening when I look at her; there is a dialogue opened up between us: I see her, she seems

to see me, I recognize her recognizing me. There is a pull between subject and

viewer, an experience far more like staring at Lady Agnew than staring at a

television screen mutely spilling out images of refugee camps in the Middle

East.

|

| Steve McCurry's "Afghan Girl" is one of the most-recognized photos of all time; via wikipedia.org |

~

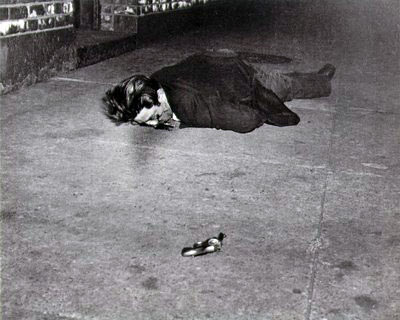

Our fascination with Weegee, I

think, stems from this capacity of news photography: to make us feel, to involve us deeply in a conversation with a freeze frame of reality. Weegee is

a master because of this ability to make us feel acutely and

powerfully—see the photo below of a corpse with a gun lying yards away. It’s a

blunt image, brisk and to the point, but its effect is powerful; in most people

(I suspect that a few feel revulsion), it elicits a weird, uncomfortable fascination. Weegee’s

placement of the gun in the frame is practically begging us to ask questions, but mere curiosity is not the selling point of the photograph.

Rather, it is fascination, pure and simple, that brings me back to this image—not

questions, but wordless wonder; I converse, however odd that sounds, with the corpse on the street. I feel a connection to the dead man and the gun that killed him.

|

| One of Weegee's best-known works, this photo depicts a criminal shot on the street by an off-duty cop; via tumblr.com |

Weegee not only knew how to make

the viewer feel acutely when it came to crimes, accidents, and general mayhem;

he also knew how to show the quieter, more familiar side of life. The ICP’s

exhibit digs into these lesser-known sections of his work—including photographs

of people sleeping on their fire escapes during heat waves, crowds of tens of

thousands of New Yorkers at Coney Island, the smiling, slightly seedy bar scene

of the Lower East Side, and a few hallucinatory, beautiful photographs of people

at the movie theatre. The element of connection is so powerful in some of these

photographs that it seems unlikely that they could possibly have been

considered photojournalism. The exhibition proves (as if anyone had their

doubts) that Weegee’s work belongs on the art gallery walls the same as any art

photographer’s.

|

| A couple kisses while a film plays (the kiss, however, was staged by Weegee); via amber-online.com |

No comments:

Post a Comment